Embers Burning in the Dry Grass

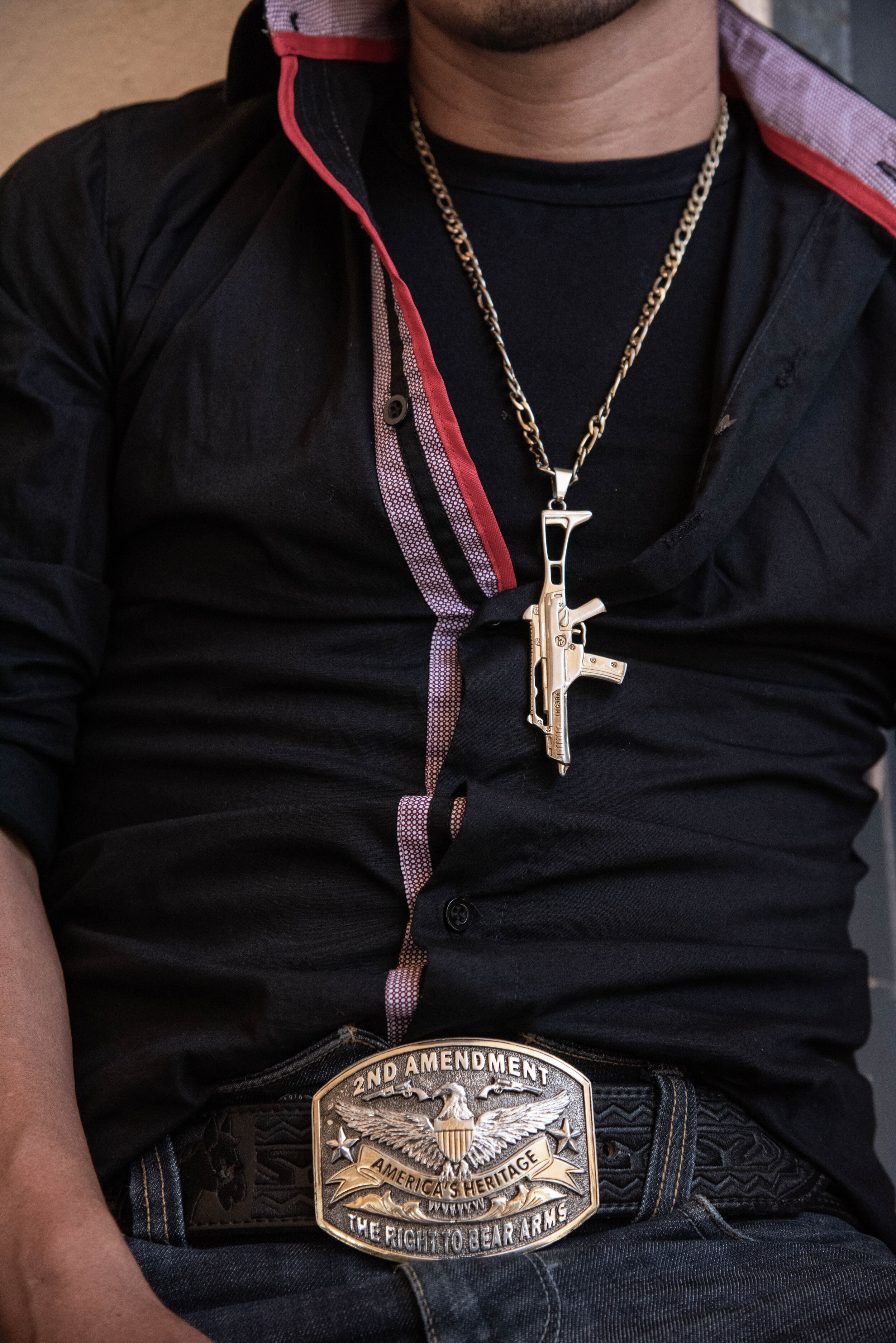

A member of the National Guard in Santa Marta, Chenalho, Chiapas.

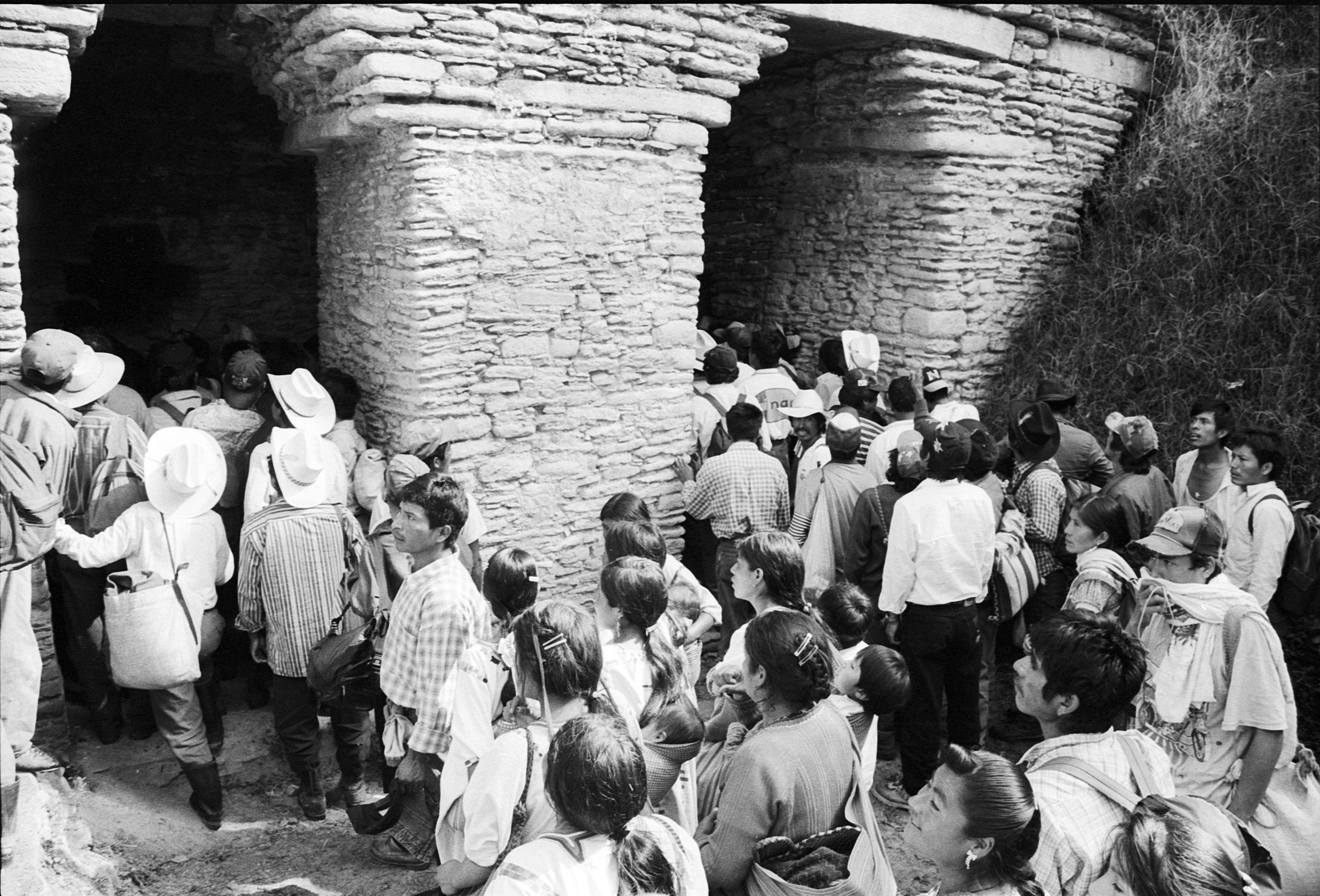

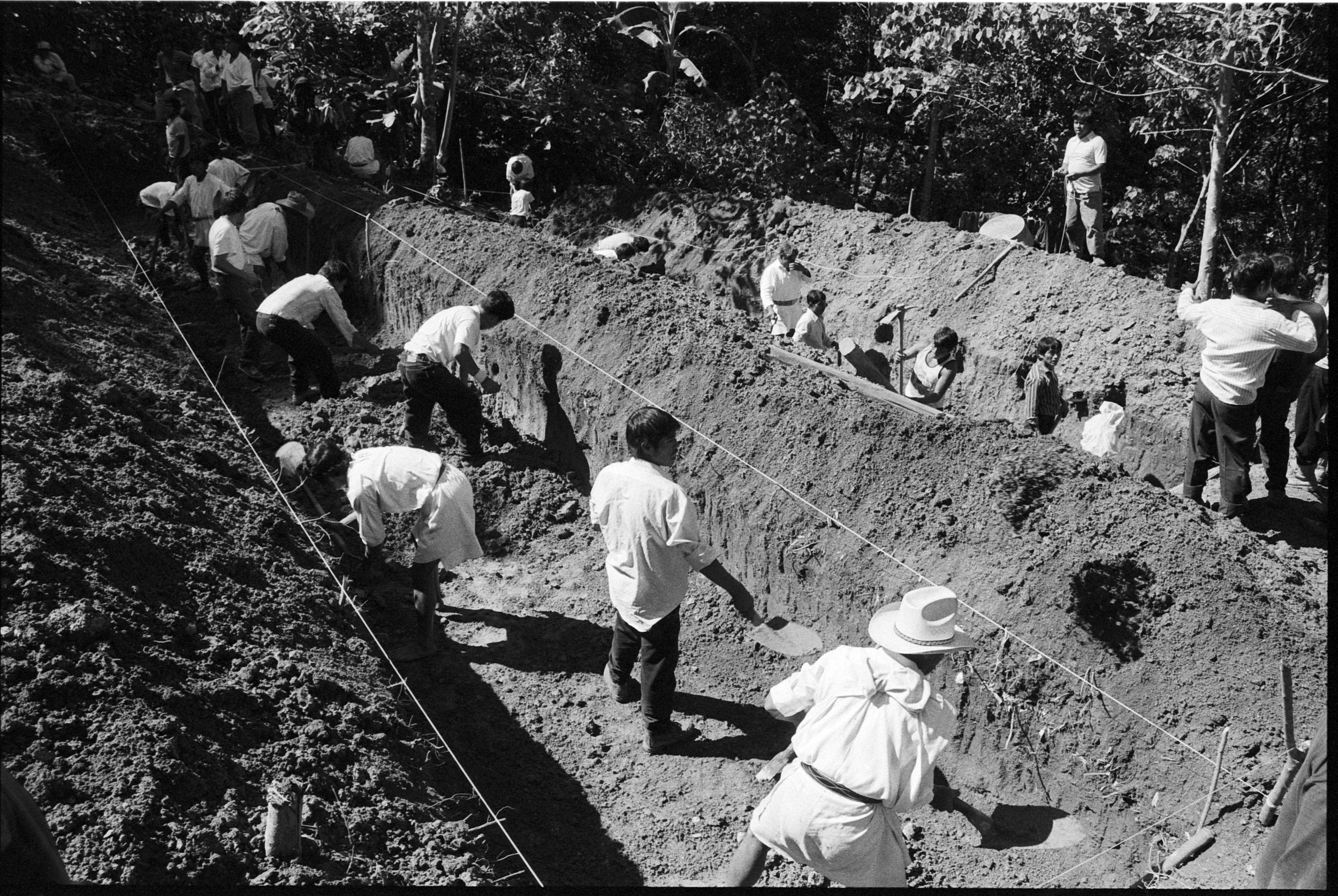

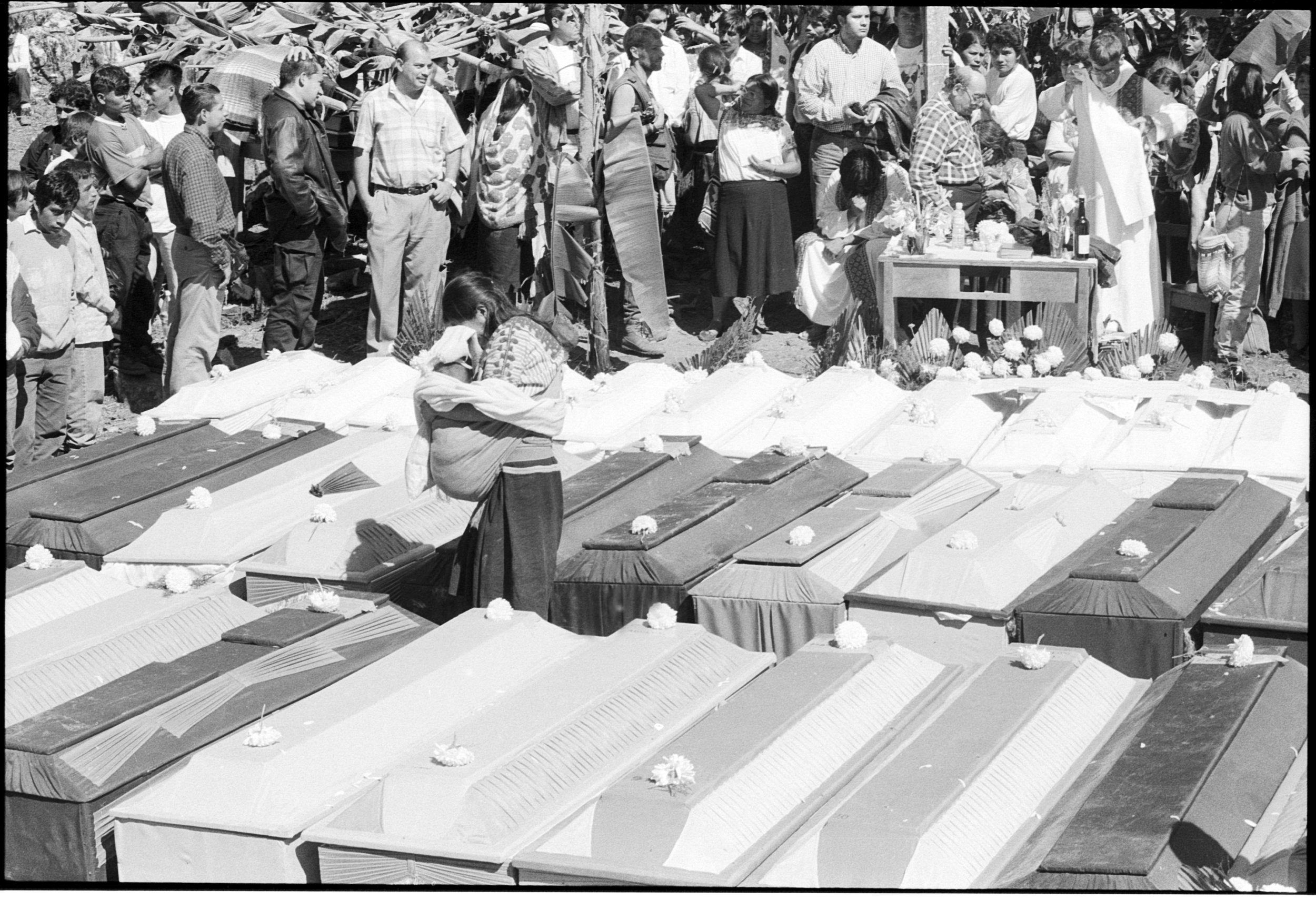

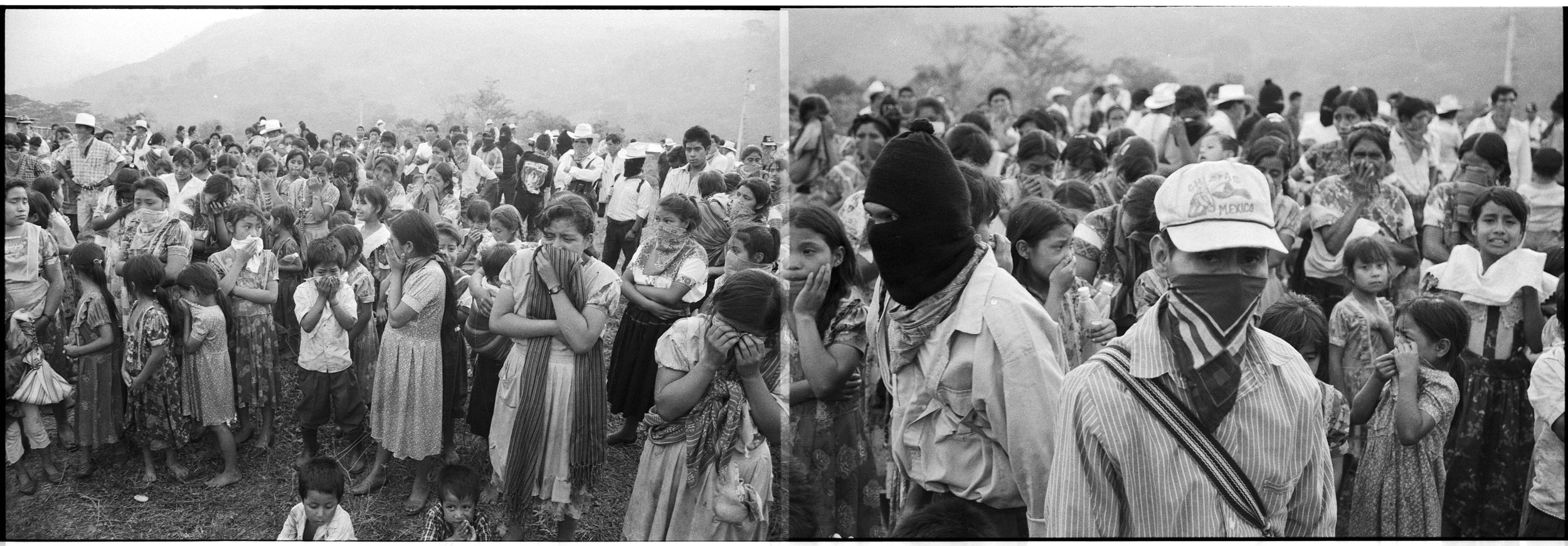

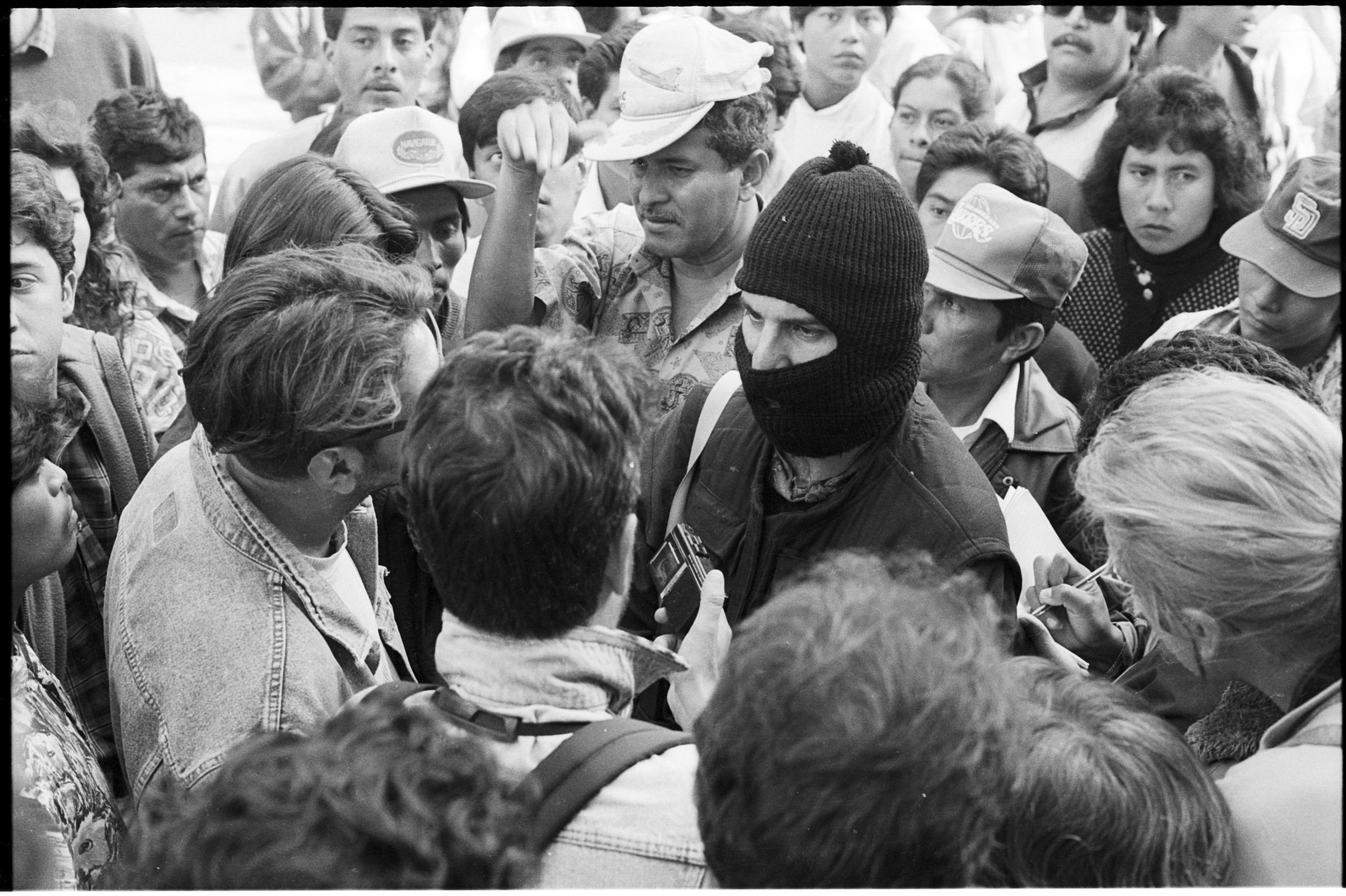

After the Zapatista uprising of 1994, the Mexican government began training paramilitary bodies to counter insurgencies and break up support for the Zapatista National Liberation Forces (EZLN). The government occupation in territories neighboring those of the Zapatista began deep divisions between communities in the municipality of Chenalho, Chiapas having serious consequences on the society and culture of indigenous people in the area. These tensions reached a tipping point in 1997, when paramilitary forces from the center of Chenalho attacked the community of Acteal on Christmas Day, resulting in the massacre of 45 people and the displacement of close to 4,000 others who supported the EZLN or those who refused to join the paramilitary bodies.

Some of the military camps set up in 1994 are still around today, however they are not authorized to enter Zapatista communities. Under the current Administration, a shift in policy naming some of these agents members of the National Guard, rather than the military, has granted them more leeway and permission to enter these communities under the guise of peace-keeping forces. I have already begun documenting this process to reveal how the military presence in the area has created a tenuous and uncertain situation, leading to a recent upsurge in violent clashes between communities in Chenalho, namely, Aldama and Chalchihuitan, who are struggling to defend their territory and customs.

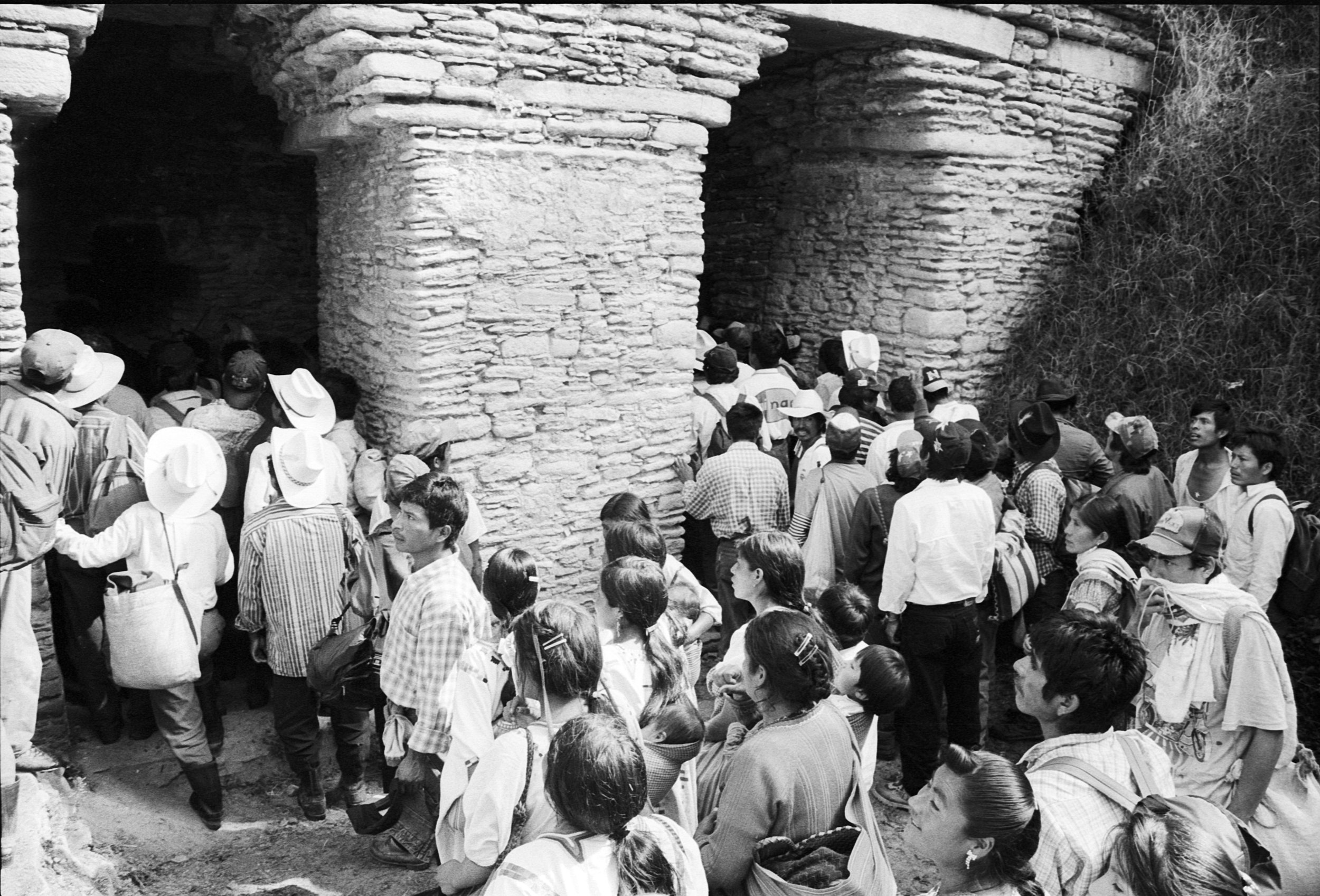

Forced internal displacement is a worsening problem in Mexico. According to the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH) Chiapas is the state with the highest population of internally displaced people (IDPs), with 6,090 people displaced in 2017, accounting for approximately 29.87% of displacement in the country. However, despite the long history of displacement in Mexico, the Federal Government does not have a policy in place to defend the rights of IDPs nor does it seem to be a political priority.

In order to advocate for the rights of displacement groups, I believe we must first tell their story to better illustrate and explain the culture of violence that has been perpetuated in this particular region. That way, the historical context can be better understood and the cycle of violence can be examined with the hope of raising public consciousness and inspiring action. By using photography to humanize the experience of internally displaced people, I hope to raise government accountability for the injustices that have taken place.